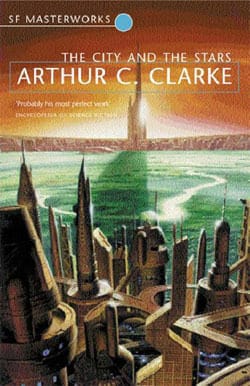

Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars and Hope

This is not a review of Arthur C. Clarke’s book The City and the Stars or really an analysis/critique of the book. It’s more a burning question I’ve had since I finished this book last summer: How can someone see humans, and their future, in such a positive light?

I read this book as part of a sci-fi writing group where we also try to read a book a month. This book was suggested as a “classic” in the genre that it would be good to read. Honestly, my initial reaction was that I wasn’t going to dig it at all, and during the whole beginning where it painstakingly describes the future world that has been created, the titular “city”, I was sure it wouldn’t pick up. But, it does and it was fine and I enjoyed it.

The thing that got me though and I can’t really shake six months later, is how much hope Clarke had for the future.

For those who haven’t read it, this book is about a city called Diaspar (a little on the nose?) where people don’t die but are reborn eternally through a Central Computer. Alvin is our main character and, I’m skipping a ton here so if you’ve read it before please don’t come at me, he leaves Diaspar, finds another human civilization called Lys that lives more traditionally off the land without immortality. The primary conflict in the book is why Diaspar won’t let Alvin leave and then why there isn’t a better connection/bond between these peoples. Again, simplifying here.

Throughout the book there’s this sheen on everything. This kind of grimy, sticky, sweet smelling shine that permeates all the moments in the book. Can’t get out of the city that anticipates all your moves? Luckily there’s a dude whose purpose is to get you through this. Can’t get through the desert? Good thing someone buried that spaceship. All seems lost? Well with a can-do attitude and the inherent goodness in your fellow human, you’ll succeed. Given the opportunity to fly into the space and explore? No, there are too many responsibilities here. You can almost taste it now, can’t you? The hope is all over the place. No one’s cleaned it off in thousands of years.

Okay, that’s a little much. I’ll admit hating on hope is a little cliché while also not being accurate to my personal experiences or beliefs. I just struggle to see the future in the positive way that Clarke does.

For me, and maybe for you too, the world doesn’t seem to be on a trajectory towards justice or goodness or hope. For me, the future seems bleak as I get close to my fourth decade on this Earth in which I have experienced a slow slide into more and more economic distress. This is even with a large increase in the floor pay my union just won (woot woot unions!). The more I read and learn about history or science or politics, the more I find myself deeply saddened by our inability to change significantly. A world where humans seem dedicated to our ever-quickening deaths through funny pictures we ask plagiarism machines to make for us.

I mean, I’m definitely negative right now, which I’m sure many of us are. Add to this my father’s death and a few illnesses and I’m not sure how to really feel hope again. But Clarke does.

And this is the part that really gets me because the book is written in 1956 based on a previous novel from 1948. These years aren’t, exactly, hopeful years. We reflect, sometimes, that they’re hopeful because they’re post WWII, but there was that whole Cold War thing at the very least. The 50s in Britain might have been good for some but not everyone; Clarke emigrated to Sri Lanka in 1956 because, according to Wikipedia, he loved scuba diving but I’ve read elsewhere that there were less intense laws regarding homosexuality. I guess either could be correct?

The point here is that Clarke is smart enough, given just a brief look at his life, to be aware of the world during this time and to see that there are plenty of signs that things might not be great. Yet he decides on hope. That’s a choice.

So, how can I decide on hope? Arthur, Arty (if I may), how does one choose hope?

This book, more than anything else, made me question my capacity for hope; what my ability was to look into the future and say, “I can imagine it kinder, more equitable, where things are better for the most part.” It happens to be low right now, but I’ve never considered what makes it low. Or high. Or what changes in my life to shift how much hope I can hold in my stomach before I become intolerable at parties. That’s felt like something I should pay more attention to moving forward. Arty helped me think about that.

I know that the book isn’t all puppies and rainbows, there’s a lot of desert inside these pages actually, but it ends with the idea that humans aren’t as selfish as I think we are. That sometimes we choose to be our best. We can choose the right thing. Those things can have profound, wonderful consequences.

After reading The City and the Stars, this is what I want to hold on to: that we can feel hope. I want to stop putting blinders on to what good people are doing, have been doing, will continue to do. I want to stop the complaining and start acting more. I want to believe there is an end where things are better and good. That the future is filled with things my child will be proud to be a part of. That I will look back and say that it was dismal there for a bit but it’s getting there. And this wanting, if I do it enough, just becomes it, doesn’t it? Even writing this out, a desire for something more hopeful in my own future, I’m fighting against my natural impulse to see it all bleaker than the day before.

So, I think to myself: What happens if it does get better eventually? Will I want to be someone who helped get it there or just the guy that whined about it nonstop? Damn Arty. Really have me thinking about things more than I thought you would.

The final thought I have on this is that if we can’t imagine it, it isn’t possible. If we don’t imagine someone given the chance to run off into space choosing to stay instead, then it can’t happen. We must think it first before we can do it. So maybe Clarke is trying, in his way, to help imagine a future, as plain as that sounds. One where we can see hope baked into it all from the start. One where we continue to grow. One where I can see it too.