Vertigo’s User and Reading a Comic Firmly Set in its Time

Trigger Warning: discussion of rape and/or sexual assault

As most comics readers, I often find myself at the dollar bins or trolling comic shops during sales to find missing parts of my collection or new series to dive into. For me, I’m often drawn to old single issues that have stories or characters I’ve never heard of before. I enjoy reading pieces that some now famous writer or artist or colorist first published in or side projects that they took up. It’s a distinct joy to find early work which usually treads the line between entertainingly silly and genuinely interesting and fun.

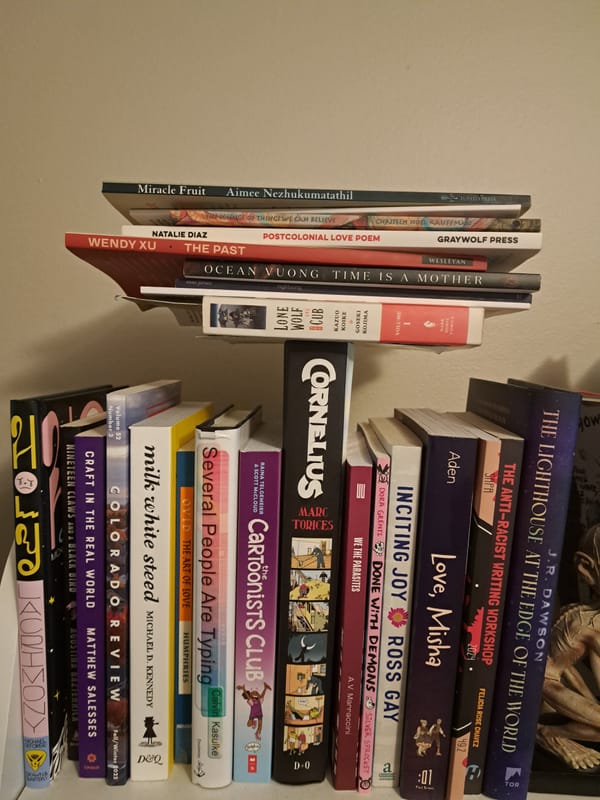

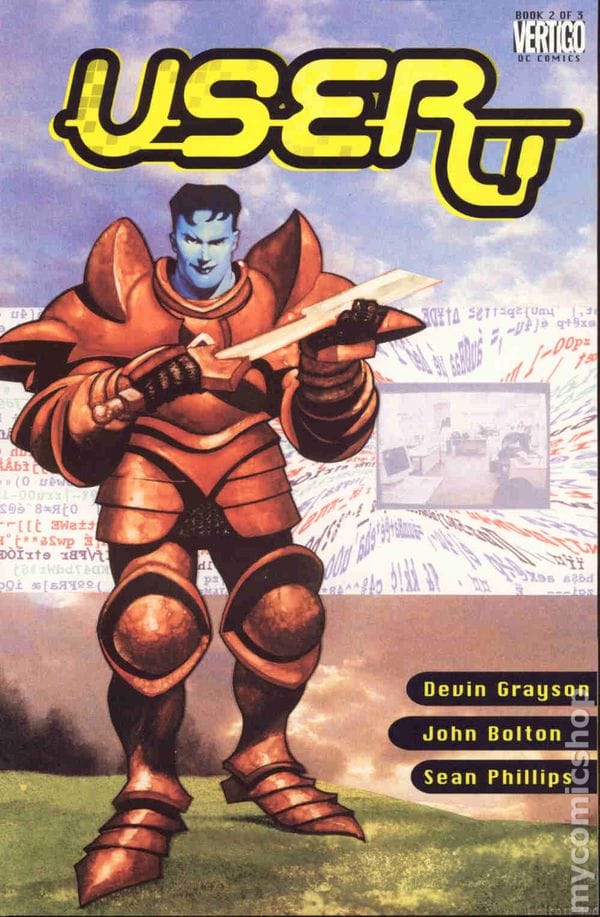

This is how I came across the three-issue series User published by Vertigo in 2001. I picked it up because I knew the name John Bolton, though I still can’t remember what I read of Bolton’s first or recently that made me recognize it, and Sean Philips who is one of the few artists I follow pretty regularly no matter what they put out. Add in some covers with code in the background and maybe the suggestion of someone slipping into the internet? I was sold immediately.

I wasn’t familiar with Devin Grayson’s work, the writer on the book, but a quick look at what she’s published seems to check out that I wouldn’t have really run into her before. Her work seems to out of the comics I’d usually read, so this was my first interaction with her writing. I know little else about this writer other than what is in User so take that for what it is.

As I went into reading the first issue, without any primer what-so-ever, I found myself confused then surprised. The book is about Meg, who’s family life is super awful and complicated (more on this later), and how she gets obsessed with an online text-based roll playing game to the point where it starts to take over her life in negative then increasingly positive ways. Not as much science fiction as the cover initially suggested, instead it’s incredibly grounded in the fantasies we entertain and how they compete with reality. The fantasy world online is drawn by John Bolton and the real world by Sean Philips.

Meg plays a French knight, Sir Guilliame, who interacts with other knights and royalty in this online chat room roll playing adventure. Here, she gets to pretend to be a male knight, in control of his destiny and life, while romancing a young woman plus another male knight. The interesting depiction of freedom from gender and sexuality is truly wonderful here. Then there are battles with randomized dice rolls and detailed descriptions of your actions. All beautifully, surreally drawn out by Bolton.

It's this play with online chat rooms that really kept me reading. Though much of the plot points involved with this part of the story seem stereotypical or obvious to a reader now (everyone is pretending to be someone else online so the head knight is a kid and another male identified knight, a young woman) I don’t think I’ve read something from early internet chat room days that was this explicit about it while presenting it as something complicated and not wholly bad. The narratives that I’m familiar with, especially during that time, where of the To Catch a Predator variety and not so much the finding love/friendship kind.

The parts that Philips draws, Meg’s real life, where a little more problematic and difficult for me to grasp. Meg has a younger sister, Annie, who is abused or assaulted or potentially prostituted to her father’s friend after her mother leaves at the very start of the comic. Though I assume this is some sort of awful quid pro quo between the father and his friend, it is not made clear what exactly is happening between Annie and her father’s friend. As the issues progress, what is happening to Annie seems to shift from sexual assault to potentially prostitution of a minor to “inappropriate touching” (still sexual assault but differentiated here because it seems to take on a less “serious” tone at times) then back and forth through various iterations of assault. My assumption is that it is something close to, if not actually, rape. The end, especially when Meg seems to “inform” her father of what is happening as though he didn’t witness it multiple times in earlier issues, makes this less clearly stated though Meg and Annie’s father remains awful. This is all to say that it isn’t clear what this abuse actually is nor how either parent is involved (the beginning of the comic implicates the mother as well). This could partially be because we follow Meg throughout the comic, and she ignores it explicitly.

Because of this lack of clarity and the seriousness behind what is happening to Annie, these moments in the text seem more like titillation rather than central to the plot or characters. They’re meant, I believe, to serve as reasons why Meg would want to escape into this digital world but it made me ask the question: Why this rather than just the neglect that she feels or, really, anything else that happens throughout the comics?

Though much of this series is dated, this seems like the part that’s dated the most and in ways that are hard to understand out of the context of when it came out. Maybe editors wouldn’t let it be more intense? Maybe there were limits to how much could be shown and still get it through Vertigo or distributors? I honestly don’t know. I’m reading it in the kindest way possible here, unconvinced that it is something nefarious but potentially unthought out.

I want to take a moment here to add a final comment on this, based on the very end of the series. At the end, Grayson does a bit of a call out or thank you to people who she interacted with online in a, seemingly, similar way to how Meg interacts with her role-playing group. This leads me to suspect that a lot of this may be based on personal experience, though it is clearly not a memoir or autobiography. This complicates my critique because it is understandable to not want to air so much dirty laundry in a story so clearly built from your real life, especially for those who may read it and know what you’re referencing. But, for those, like me, who are not privy to that information, the lack of clarity the reader is given feels like a kind of withholding that doesn’t add to the story but, instead, creates a hole where what is missing feels vitally important yet I’m told to ignore it anyway. I never need to see abuse on a page for it to be valid. All expressions are valid, even this one. Yet, when it isn’t named or consistently clear in a fictional narrative, it makes it difficult to know how serious the creators are taking it. It makes it easier to read the creators as being sympathetic to the abuser or using the abused as plot device to get emotional investment from the reader.

Which is unfortunate because the ways in which Meg uses the internet and explores the web, are incredible. There’s even a plot point where Meg has to run to another player’s house to use his computer because her father has disconnected the phone line. Oh, the days of dial up.

This conversation around identity online, connections with others who share your niche interest, and expressions of sexuality in online spaces is incredibly fascinating. The complex way that User explores the connection between people who would never have the chance to connect because of geographical distance or age or background is a testament to how this book can see the positive interactions that digital communication can give us. The ways that the internet can foster connection and discovery rather than the typically negative interpretation of connection online which often ends with calls for me to go touch more grass (which I get), is needed too.

Sir Guilliame exploring a bisexuality identity online and Meg’s queerness that becomes evident at the end of the book are wonderful examples of how the digital space can open more than it closes. The whole conversation that surrounds the end of the final issue where Meg meets another player at the airport discovering that she, too, is a woman who plays a male character in the chat, is all about the potential of the internet, stories, games, and the way these can weave together. This end, while sometimes a little heavy handed, is a wonderful shoutout to the ways in which we can find ourselves, or loose ourselves in the best way, within the confines of an internet chatroom.

At the end of reading this three-issue series, I was transported back to getting my first desktop computer, to the Yahoo chatrooms, and the awkward connections I was trying to make as a teen. Though I didn’t spend nearly as much time in chatrooms as Meg does, nor did I get too into text-based roll playing games, the early internet was a place where I could pretend to be who I wanted to be. It was where I played out different identities and discovered who I could be in the real world. It was where I found out that that line between digital and real was thinner than I imagined.

Overall, User is a comic that sits in a place in time that doesn’t exist anymore. That, alone, makes it worth the time for a revisit and the reason I’ll always go digging in a long box of dollar comics. You never know what artifacts and adventures you’ll find.